Not every recorded statement is created equal. It might seem as though you won’t get much variation on a task that involves asking questions from a predetermined script, but you’d be severely underestimating the impact an adjuster has on a statement. In our Adjuster Skills Case Studies, we’re examining actual recorded statements to identify and correct the mistakes adjusters make. It’s our hope that reading these case studies will help you improve as an adjuster, as well!

In this case study, we’ll be examining an adjuster who fails to keep control of the interview. As we pointed out in our blog post on the Six Essential Statement-Taking Skills, some of their difficulties invariably stems from some failure to adequately set expectations for the interviewee before the statement begins, and we’ll point out those effects when they come. While we won’t share the entire file, and proper nouns have been changed for our clients’ protection, we will look at three excerpts to get a picture of how the statement could have been improved.

Excerpt 1

The first point of controlling an interview is setting expectations for the interviewee. This happens before the recording begins, and should set up the interviewee for full cooperation. Full cooperation, in the context of a recorded statement, means that the interviewee is answering questions in as much detail as you ask them, because you have gained their trust that this is the most efficient way to memorialize their recollection.

However, many adjusters, like this one, adopt a more passive approach, take-what-the-interviewee-gives-you approach. They think it avoids conflict, but what it really means is they are either unable or unwilling to confidently assert their approach. We see in this example what that results in. Instead of asking questions to establish the important elements of the accident location, which the adjuster should begin with, they kick off the accident details with “Can you tell me what happened in the accident?”

Fortunately, the interviewee is relatively helpful by providing location details as they explain. Still, by choosing to forgo a more structured approach, the adjuster is guaranteed to either miss details or spend time confirming or qualifying details shared by the interviewee. This exchange takes about 90 seconds, and all it confirms is the driver was stopped in the southbound lane of Green Terrace, and that the other vehicle was coming north. This is all actually stated in the first line, but because the interviewee is given no structure, the adjuster has to spend their next few questions clarifying their own understanding.

Again, the adjuster is fortunate that all the details are present, they just need to clarify them. It’s entirely possible that the interviewee could have left out important details entirely, and the adjuster would need to backtrack to seek those details out. What is more problematic for this particular interview is the precedent that this open approach sets for later in the interview.

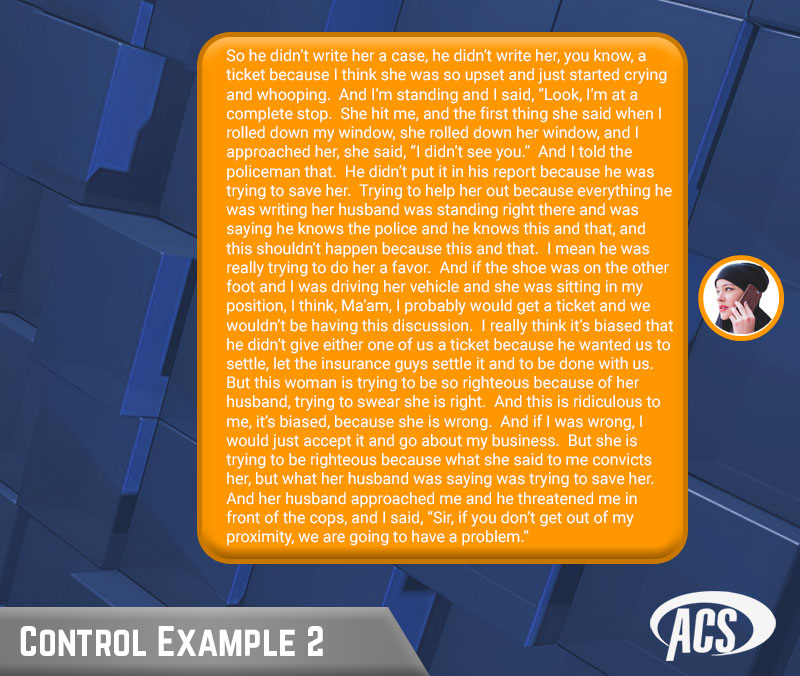

Excerpt 2

In this excerpt, we see the proverbial chickens of inviting the interviewee to share their recollection without any structure begin coming home to roost. In this example, our adjuster asks a question, and then receives four responses to it. The first answered her question- she should have moved on to another question. Instead, the interviewee has grown accustomed to having the momentum in the conversation, and continues on.

Her second response can be considered adjacent to the first, as it qualifies and illustrates the distance that she was over the line. Her third response moves into a post-accident conversation. We’ve now moved into territory that is entirely unrelated to her original question, and still no interjection from the adjuster. Finally, in the fourth response, we get a whole jumble of information- a little on the impact area, a little post-accident detail, and a brief attempt to establish some cause with the bit about the cellphone.

You could argue that all that information should be collected eventually, and a good adjuster will be listening and collect all of those details accordingly. A better adjuster would collect those details in an organized fashion, so that the statement is significantly more useful to everyone who uses it over the life cycle of the claim.

The jumbled information isn’t great, but what is worse is the adjuster hasn’t taken any action to regain control of the interview. The longer this goes on, the more momentum the interviewee will have, and the more jarring an attempt at control will become. This is over 60 seconds of audio where the interviewee asks a single question, and more than half of that audio is spent discussing elements unrelated to the question. The adjuster is absolutely complicit, offering little more than “Okay” and “Mmhmm”s as a token indication that they are listening. Maybe they don’t care, maybe they’ve stopped listening, maybe they don’t appreciate what the culmination of this approach may be.

Well, let’s show you.

Excerpt 3

Oof.

This is only about a 60-second excerpt that we’ve collected for you, but there are two more that we don’t show here. At this point, the adjuster has lost full control of this interview. The contents of this excerpt are almost entirely repeats, as the interviewee has already provided answers about the driver’s comments post-accident, the behavior of the police, and the actions of the husband. The interviewee has gotten comfortable in using this stream-of-consciousness format to memorialize the accident, and to try to wrest them away from it now would be uncomfortable for them, and could even invite hostility.

The remarkable thing is the adjuster may not be pleased with this development. They may now start to feel trapped. When this conversation ends, the adjuster might remark to those around them that they simply “couldn’t get this person to stop talking” or “she kept repeating the same things over and over.” Their mind may begin to wander to the rest of their responsibilities that they need to get back to, or how frustrating it is to have lost agency. When they do get a chance to ask another question, they are more likely to take shortcuts and miss information.

The adjuster may feel trapped, but this is a prison of her own making. Furthermore, the interviewee is trapped, too- they don’t know what information the adjuster is still looking for, they know they’re repeating information but they’re not sure what the adjuster might have missed or have deemed unimportant. They’re ready to get off the phone and move on with their life, the same as the adjuster.

This is the culmination of a loss of control. This statement probably took anywhere from 7 to 10 minutes more than it needed to. That may not sound like a lot of time, but how many statements do you take every day? Every year? Not to mention how much longer it will feel- for both parties- given the level of frustration.

Practical Advice

1. Set expectations before the interview.

“Control” is not about exerting some measure of authority- it’s about maintaining efficiency in a potentially fraught or frustrating task. Furthermore, it’s intended for the benefit of the interviewee- the more they cooperate, the faster the interview will go and the more useful the information gathered will be. It’s critical that you help the interviewee to understand this before ever turning on the recording.

What exactly you tell them is up to you, but there are two key points you should express. One, the interviewee should know that the purpose of the statement is for the interviewee to be able to memorialize their recollection of the incident. Two, they should understand that the process of the statement- the questions that you will ask, the direction that you will give- is all designed to support that purpose, so it’s in the interviewee’s best interest to follow it accordingly.

2. Use direct questions, with precise intents, to establish a question-response rhythm for the interview.

Let’s look back at the start of the interview.

ADJ: And just in your own words, Miss Riggins, can you tell me what happened in the accident?

This question is, quite simply, a roll of the dice. Starting with this question, before you’ve established any of the location details, is especially dangerous. It’s possible for the interviewee to lead you to the information that you need, but you’re basically guaranteed to take more time. And in the worst cases, you’ll miss information entirely.

To understand an accident’s location, you’ll need to understand the type of road, where each vehicle was before and at the time of impact, and any other relevant environmental considerations. Ask directly about these factors, and then follow-up with any necessary clarifying questions. When you understand a factor fully, move on to the next one.

3. If an interviewee starts to stray, set them back on track.

This may not feel very comfortable to you, and it may take some practice. It can feel confrontational, but it doesn’t need to be. You’re not wresting agency away from the interviewee; you’re guiding the interview to its intended destination. The longer you wait to make a correction, the more uncomfortable and difficult it will become. In the case of this example, things snowballed so much that a course correction probably became impossible, leaving both the interviewee and the adjuster feeling trapped.

It doesn’t need to be that way. This is precisely why we recommend setting expectations before the interview- your interruption can be a mere reassertion of the expectations. Something like, “Excuse me for jumping in, but I have a few more questions about the accident location before we get into how the accident happened.” This simple statement both reminds the interviewee that you are in control of the interview while simultaneously assuring them they will have an opportunity to say what they want to say.